Just Another Day in Baghdad

Note: I posted about some of this stuff before but it deserved a more extensive re-telling.

Awakening on a lumpy bed in my dingy apartment building just off Karada Street I can hear the street sounds of cars and propane sellers tapping a clanging beat as their donkey carts roll by. I always have a fleeting moment of wistfulness for the comforts of my old bed in Happy Valley back in Port Townsend, Washington. But there is no time for that. I need to be up, squeezing out the laundry I left soaking last night and make a hasty breakfast of eggs and potatoes in the broken skillet in what passes for a kitchenette here. I long to live in a real house again but as I rush over to the Aghadeer Hotel only a few blocks away, I am greeted by Baha, the hotel clerk, with a terrible story.

A week ago, I was given a tour of Baha's lovely home and garden on a quiet side street in central Baghdad. Baha owned a shoe store before the war and lived comfortably with his family in an upper middleclass neighborhood. But with the war and the looting that followed, Baha lost everything but the house. Now struggling to make ends meet, Baha is thinking of renting out a few rooms in his big house. I am more than a little interested. But on this day, Baha tells me of a neighbor who had been inviting Americans soldiers to his home. Someone apparently did not approve and placed a grenade under the man’s car. "To teach him a lesson," Baha says shaking his head. I'm no soldier but I doubt that Baha will still consider the idea of renting out any rooms to me.

I leave Baha and the lobby behind and head up to my friends room. Lorna Tychostup, my travel partner here to Iraq and a freelance photojournalist, is on her last week here in Iraq. "I’ve been here over a month," she cries in frustration, "and I still don’t know what’s going on!" With her is Alaa, a lovely 28 year old Iraqi woman, who has been our translator. Alaa will take us to two refugee camps today, one nearby at a place called the Air Force Club where we will pick up a man named Abbas who lives there and then another near the Mukahabarat, the old Iraqi Intelligence Agency (which incidentally is across the street from the Zoo). Both areas were bombed by the U.S. last year, then looted, and then occupied by squatters. Most are simply poor people fleeing from worse situations that simply saw an opportunity to carve out something for themselves. Some were evicted from their old homes because landlords wanted more money than they could afford. Some just came because they wanted free rent. We even heard of one story of a family that decided to move to a refugee camp because they could earn more money by renting out their house.

It's hard, walking through these burned and blasted places, to understand that this was a better option for these people. And there is a definite hierarchy about these places. Abbas and his family have taken over a house, but there are others living in former offices, hallways, storage rooms … they use scrap wood, blankets, and bits of wire and refuse to delineate their space. Their children play among piles of broken glass, concrete and insulation. In one location, a single water pipe servers the needs of many families.

At the Mukahabarat camp, we meet a woman and her son who is suffering from some undiagnosed nerve dysfunction that has crippled his legs. Have they been to doctors? Yes, many, each says something different and the money has run out. They look to us to help them and we have no idea what to say. Lorna is in tears but I'm filled with just an impotent anger.

And yet it's hard to believe everything you hear. I ask if the children go to school. "No," said the spokesman of the Mukahabarat camp, "No school." But moments later, I see several children walking off together in school uniforms with book bags tossed over their shoulders. Over tea in this man’s house (the biggest and grandest building in the camp despite the gapping holes where windows and lighting fixtures have been ripped out) Alaa, our translator, whispers to us.

"I don’t think this man is honest. He is not like Abbas. Maybe he wants your help so that he can benefit the most.” We smile and caste sidelong looks at one another and finally make our escape.

It's past midday, so we grab a taxi and ask Alaa and Abbas to drop us off outside the Green Zone. Lorna needs to track someone down who works near the Palace. This will be my first entry into a huge swath of Baghdad territory that is controlled by the coalition forces. We see the soldiers making their patrols in the streets of Baghdad and we hear their helicopters flying low overhead from time to time but I've been here several weeks and I've never even talked to an American soldier. Early in the Occupation, we've been told, they could be seen everywhere, drinking tea in the shops and talking to people. But the mood is decidedly more business like these days. Entering the checkpoints, Lorna whispers too me, "Just look like you belong here." I had to laugh. This particular check point is a bit lax … we are searched but when they ask for ID, we just tell them we have none and they wave us on (there are other entry points in which you will be asked for ID and searched no less than three times).

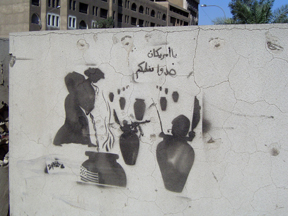

Once inside, the crazy traffic of Baghdad (which has been made crazier by the fact that the coalition has locked up so much of the city within its protected zone) is left behind. The Green Zone is downright mellow. Here you can hear the bird songs and smell the blooming flowers of spring … without the acrid top note of diesel fumes. It really is another world in here and one that seems to be quite out of touch with the world we live in day by day (we’re told that Greenies call it the Red Zone). You’ll meet the darndest people in the Green Zone … on this day it is an Irish National recently transferred from the Hague to work on the Iraqi War Crimes Tribunals. We poked around a monstrous palace building (belonging to Oday or Qusay … I can never keep them straight), that had been hit by two bunker-busting bombs. Workers were inside pulling out doors, chandeliers, toilets … anything of value. We walked through the blasted building, crunching on Plaster of Paris and thousands of cut glass chandelier parts. In one room was a huge painting depicting some momentous occasion in Arabic history. Coalition soldiers had added their phallic graffiti to the story depicted there. As we wandered through we met two Americans strung with dangling badges and holstered weapons.

'Oh no,' I thought, remember days in my youth where I was caught loitering in forbidden places,

'they are going to throw us out.'

But when we draw close, Lorna asked them who they are and they tell us that they are Pentagon analysts.

"We’re doing exactly what you’re doing," the younger man laughed, "We’re poking around and taking pictures!" Later on, the older man approached us, excited as a school boy, to show us a prize find that he plans to hang in his Pentagon office … a large plaster plaque in arabesque curlicues bearing Saddam Hussein’s insignia. Finally, our fear of the depleted uranium that may be lurking in this building gets the better of us and we decide to go looking for food.

I don't know what other delights the Green Zone has to offer but it does include several internet cafes, a market selling a comprehensive selection of tourist goodies to tempt the boys in green and at least one Chinese Restaurant (my advice: avoid the egg rolls).

But now it's getting dark, the witching hour here in Iraq, so we start looking for an exit. We are only across the river from where we are living but the Green Zone is a completely self-contained world with a limited number of entrances and exits. We're confused and turned around but finally make it to a troop and tank-guarded gate. We smile at the boys in green as we pass through, hailing the first cab we see to take us home in the twilight-tinged smog of early evening.

After such a day, we usually head up to the rooms and download the day's events to our friends at the hotel, trying to make sense of it all. Then we’ll check email (we are one of few low-budget hotels that has internet … thanks to a grouchy Hungarian reporter living on the top floor) and plan the activities for the next day. Another refugee camp visit, a meeting with a women's activist group, or a trip to the Radiation Center to interview its Director? By the time it’s full dark, it’s time for me to return back home. I’ll have a few hours more of typing up notes, studying my Arabic or practicing some Tai Chi to the droning sound of the generator outside my window before crawling into bed and catching a few hours of fitful sleep.

It’s been just another day here in Baghdad. Each one adding both confusing and clarifying bits of information to the puzzle that makes up the place.