Kurdistan in June is Golden and Stunning

We left for Erbil on Friday, June 4th. David & James two journalists and A my translator had gone up on Wednesday. I traveled with another journalist named Dahr and his translator/driver Harb (Harb is Arabic word for war and given that this man can be argumentative, unwilling to listen and always sure that he is right while you are most assuredly wrong, I think is name is quite appropriate. Regardless, he is a very nice man and according to Dahr an amazing "fixer").

First we visit with some friends of Harb in Kirkuk that lies a little over an hour south of Erbil. Harb is a retired Iraq army officer. His friend could only be described as something equivalent to the English batman. We spent time talking about the situation in Kirkuk, which is primarily characterized, according to Harb’s friend (a Turkmen) as a fight for control of the city between Arabs, Turkmen and Kurds. There is an American military presence here but unlike Baghdad, it is less visible.

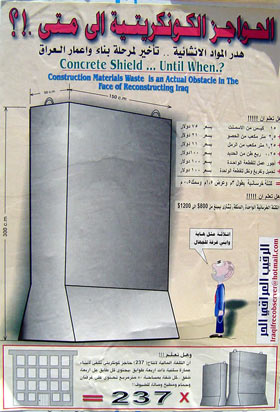

In fact, as you go into Kurdistan, that is your first impression. No U.S. Military. No patrols, no American-manned checkpoints (though there are loads of Peshmerga/Kurdish police checkpoints … in fact more than I am used to), no helicopters buzzing the roof-tops. The second thing you notice is that the cities and towns look cleaner and more orderly and there is a lot of economic activity. There are few concrete barriers set up and almost no razor wire. I’m in a foreign land, where many people don’t even speak Arabic, and it felt almost normal to me. I hadn’t realized how oppressive the atmosphere in Baghdad was until I came north. It was like an invisible weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I started to dread the return to Baghdad.

That first day, we drove to the Chwar Chera Hotel. I had been offered a free place to stay in Erbil at a Kurdish friend’s house and was told that the manager of this hotel was a relative and could help us get settled at the house. Kamran was a bit stiff at first but a loosened up over lunch in his hotel as Harb and he began an extensive discussion/argument about the future of Kurdistan. Kamran was in the camp that called for independence.

"Yes, we are all brothers, Arab and Kurd," he said, "but there should be no problem if, as brothers living in a crowded house, we decide we want to move out and find our way on our own."

But Harb is a true Arab patriot. Iraq is Iraq and should not be split asunder. If the Kurds go, what will stop Sunni, Shia, Turkmen, and Assyrian from breaking up? The argument ranged over the gamut of Iraqi/Kurdish history. Saddam did this. Saddam did that. Barzani did this. Barzani did that. Talibani did this … etc. etc. etc. They really weren’t getting anywhere and I was starting to worry that Harb was slowly wearing upon the hospitality of our host.

During the fray, I wrote on a piece of paper (which I later read to them) the following:

As Arabs, if you know the history of the Kurds, you should understand the passionate desire of the Kurds for independence. If you do not want the Kurds to separate from Iraq, how can you prove to them that their history will not be repeated? At this point it should not be up to the Kurds to capitulate to the Arab sentiment of unity. It should be up to the Arabs to prove that that unity will protect the rights and life of the Kurdish people and ultimately serve their interests better than independence. You can not enforce your vision of unity upon them … if you do they will always fight you.

But living up to his name, Harb could barely listen. Dahr and I eventually intervened before Kamran was driven to his wits end and both shook hands, agreeing to disagree. After getting settled into the house of my friend (a large, slightly rundown house with a big garden) we took off for Shaklawa, a garden city about a half hour from town. There, by chance, we ran into our friends who had left two days before and were able to get some tea overlooking the town before heading back to Erbil. It was Friday, an Arabic weekend, so people were everywhere picnicking beside the roads and there was quite a jam getting back into Erbil.

The Gang at Shaklawa

The Gang at Shaklawa

My one main agenda for wanting to come to Erbil was to visit the Italian NGO called "Emergency." Dahr and David were also interested in go, so we hooked up and visited them on Saturday

(see my post on Emergency below). In the evening we headed for the city center and the old Souq and the Citadel that sits atop some high ground in the center of the city. I do not pretend to know much about Kurdish history, past or present, but I was told that Erbil is very old and the massive walls of the Citadel have seen many conflicts in the past. There was, according to Harb, very little fighting seen in the major cities of Kurdistan during the recent conflicts between Iraqis and Kurds, but this was not true here in Erbil, which saw fighting at the Citadel. There are two flags flown prominently here. The Kurdish flag (which makes Harb’s blood boil to see) … with its three horizontal bars of Red, White and Green, a many pointed sun in the center. And the yellow flag of Barzani which bares the letters PDK (Patriotic Democratic Party of Kurdistan) for his party. Kurdistan, in addition to conflicts between Kurd and Arab, has seen fighting between the two most powerful Kurdish families … the Barzanis and the Talibanis. Erbil and the surrounding area is controlled by Barzani. Sulaimaniya is controlled by Talibani and flies the green flag of the PUK (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan).

Dahr & Sophia in Erbil from the Citadel

Dahr & Sophia in Erbil from the Citadel

PDK & Kurdish Flags Atop Erbil Citadel

PDK & Kurdish Flags Atop Erbil Citadel

Honestly, trying to understand this internecine Kurdish conflict is more than I can handle at this point (this trip was supposed to be a break for me!) and I would be happy to find anyone who can explain it in some succinct and comprehensive way. When we are stopped at checkpoints, we don’t know if we are being stopped by PUK or PDK Peshmerga. Is this a Barzani man or a Talibani man? And Harb spends most of his time carping about the fact that no one speaks Arabic here and they refuse to fly the Iraqi flag (unless it is to show it in its previous incarnation that has removed the "Allah Akbar" … placed there by Saddam Hussain). Suffice it to say that Dahr and I are neophytes in this area and Harb is less than a reliable source since who would tend to wish ill will on the whole lot of them.

There rest of our trip has been truly a vacation … drives through the amazing Kurdish mountains (some of them still baring snow), rolling fields of wheat, sunflowers and oleander, stops at Galli Ali Bek waterfall, which is tiny in comparison to the Bakhal falls, that latter formed from a large underground river that comes crashing out of a mountain side. The rivers here look like a kayakers dream. The Big Zab, laden with silt, sweeps through amazing country dotted by here and there by small herds of goats, sheep, and cows.

Bekhal Falls - with restaurants and shops built around and sometimes over the falls.

Bekhal Falls - with restaurants and shops built around and sometimes over the falls.

Before coming here, someone told me that when they refer to the cradle of civilization, they are really referring to Kurdistan. Seeing just a small part of it, I’m sure they must be at least partially correct. It is June and Kurdistan is golden and stunning.

Unfortunately, my memory if Kurdistan will also be mixed up with the war, for we had trouble when we got to Sulaimaniya. In the downtown bazaar area, Harb left his car in the street as we went to secure lodging. Upon returning we found that the car had been towed away. Dahr and I went to find an internet café and Harb went to go get his car but when we finally connected with Harb again, he found him seething in anger. His car had been badly damaged and he himself had been interrogated by Peshmerga. A car bearing a Baghdad license had made the Sulaimaniya police nervous In attempting to search the car for explosives, they dented the trunk, smashed the driver side window, ripped apart the rear interior (apparently they hadn’t been able to get in through the trunk … though they sure tried), cut the fuel line and the ignition … and for good measure they snapped off the antennae.

We estimate that they did about $500 (Dahr thinks it’s more like $1000) of damage. Of course there will be no compensation and Harb, who is living on a pension, is not in any position to be able to pay for the damages. Dahr and I feel heartsick because the only reason Harb is here is because we asked him to drive us. Dahr has asked a friend with the organization Global Exchange to set up a fund to help Harb out. I’ll get the information on my web log in the next few days. At present, we sit in our hotel room in downtown Sulaimaniyah, listening to the noise off the street below and waiting to hear if Harb can get the car at least partially repaired so that we can start our journey back to Baghdad.

Emergency

My one main agenda for wanting to come to Erbil was to visit the Italian NGO called "Emergency." They run a clinic for victims of war. But I found that it was more like a complete hospital and offers a level of care rarely if ever seen in Iraq (or in some Western cities for that matter).

Emergency has been present in Northern Iraq since 1995. Originally they conducted surgeries in the village of Choman close to the border with Iran. Later they opened two surgical centers in Sulaimaniya and Erbil, each with over 100 beds. They also have a network of first aid posts for providing outpatient treatments. In addition they have a Center for Rehabilitation, Prostheses and Social Reintegration where over 1,600 landmine amputees have received prostheses and rehab since it opened in 1998. Emergency also run centers in Cambodia, Afghanistan and Sierra Leone.

In Iraq, their staff is all Iraqi/Kurdish. There was only one Italian administrator present at the Erbil center when I was there. What was most refreshing to see was the emphasis placed on nursing care. Each unit was well staffed with nurses. This is a rare sight in Iraq these days. Since 1991, nurse salaries slipped below the level that made it possible for people to work in this field. You rarely see nurses in hospitals in Iraq but at nearly every bedside you’ll see a relative sitting who tries, thought they have no training, to provide care to the patient. At Emergency, there was a man who had been operated on by an American doctor in Kirkuk. He was then left in the care of his relatives who were given little to no instruction and who never moved him in his bed for forty days. He developed horrible bed sores and was finally sent to Emergency. The nursing staff there cleaned his sores and move him every two hours.

"We believe that healing," said Sabrina de Rosa, the Italian nurse with Emergency whose main focus is the burn unit at the Center, "is the job of the nursing staff."

I was very impressed with Emergency. Rather than just a piecemeal approach to providing care … flying in some doctors to perform a few surgeries and then moving on, they have set up a long-term operation which covers everything from surgery to rehabilitation of the victims of war, the majority of which are civilians. They are also helping to provide education to hospitals and schools and work to promote a culture of peace that will one day ban the use of antipersonnel mines that remain an inhuman, indiscriminate and persistent weapon of war.

If you want to learn more about Emergency or make a donation, here is their contact info:

Emergency

Via Bagutta 12 -20121 Milan, Italy

Tel. + + 39 02 76001104

Email: info@emergency.it

Web: www.emergency.it